The arrival of the Central Pacific railroad terminus at Oakland in 1869 heightened the need for a nearby link to shipping in San Francisco Bay. Consequently, two piers that were spaced 750 feet and extended two miles out into the bay were built, and the area around them was dredged to form a shipping terminal.

The original Oakland Harbor Lighthouse sat on eleven wooden pilings, which had been driven into the bottom of the bay off the end of the northern pier. The lighthouse was similar in style to several of the original California lights with a central tower that extended through the gabled roof of a rectangular, two-story dwelling. The lantern room housed a fifth-order Fresnel lens, and the station was activated on January 27, 1890. A fog signal for the station, in the form of a 3,500-pound bell, was mounted on a wooden walkway that encircled the dwelling. The bell, which caused the lighthouse to shudder when it was struck every five seconds, was located just ten feet from one of the keeper’s beds. Adjacent to the bell was a water tank for storing rainwater captured on the dwelling’s roof.

As the station was surrounded by open waters, the keepers had to rely on a small rowboat to obtain supplies and tend the light on the south pier. One morning, the Southern Pacific Railroad’s 294-foot side wheel paddle ferry Newark paid an unannounced visit to the station. Keepers Charles McCarthy and Hermann Engel were on duty, when Engel’s wife spied the ferry heading directly towards the station. The Newark smashed one of the lighthouse’s support piles and a platform brace, but nobody was hurt in the incident. The enraged captained yelled at the keepers while backing his vessel away, even though he was clearly at fault.

After just over a decade of operation, marine borers had weakened the wooden pilings under the lighthouse, and rocks quarried near the lighthouse depot on Yerba Buena Island were brought in to try to stabilize the foundation. By 1902, the stability of the light was questioned, and the Lighthouse Board decided to build a larger structure nearby. This time, huge concrete-filled steel support cylinders with a diameter of four feet were used to thwart the marine borers.

The second lighthouse was a nearly square, two-story structure built upon a steel beam decking that rested on the support cylinders. The bottom floor of the lighthouse was used primarily for storage, while the upper floor was home to two keepers and their families. From each of the four walls, the roof sloped upward to a short square tower located at its center. The new lighthouse commenced operating on July 11, 1903, with the fog bell from the original lighthouse mounted on the second story’s balcony.

After the completion of the new lighthouse, its predecessor was declared a navigational hazard and had to be removed. In February of 1904, the old lighthouse was auctioned off, and the winning bidder was required to remove the entire structure, including the support pilings, within thirty days. The local press bemoaned the loss of the familiar lighthouse: “For many years this has been the guide of the night ferries, and during storm and fair weather, fog and moonlight, it has shone steadily and lighted the deep-sea liner in and the crawling bay scow schooner by. … The passing of the old light will be a source of regret to all lovers of the Bay, as it has grown into the affections of the constant user of it. This harbor light was the one to which the Oaklander’s eye always turned on the night ferry, and its merry gleam lighted many a happy party on yachting back to port.”

As commerce in the area grew, the Western Pacific Railroad’s ferry slip was extended to encompass the lighthouse. The Coast Guard photograph at right shows the wooden lighthouse, enclosed in the end of the pier. The pier extension simplified life for the keepers, as they could now reach the lighthouse by foot or car, rather than the station's rowboat. Transcontinental railroad connections were also now available for the keepers just a few steps from the door of the lighthouse.

Although the keepers lives were certainly simplified by the pier extension, their jobs were still demanding and even dangerous. On August 26, 1923, a stiff west wind caused a fisherman’s skiff to capsize just off the northern pier. Keeper Charles H.A. Brooke witnessed the mishap and quickly went to the rescue of the floundering fisherman. Brooke’s effort was later praised in the “Lighthouse Service Bulletin.”

Myron Edgington was in charge of the Oakland Harbor Lighthouse in the 1950s. By this time, the Coast Guard had taken control of the country’s lighthouses, so Edgington’s assistants were two Coast Guardsmen. Edgington had served in the Navy and at the Mile Rocks and Point Vicente Lighthouses before accepting a transfer to Oakland. In his spare time, Edgington practiced the old seafaring craft of macramé, making beautiful mats and tablecloths for the station. Keeper Edgington and his two assistants received their chance to perform a rescue operation when two Navy fliers, likely from the nearby Naval Air Station Alameda, plunged into the water near the lighthouse.

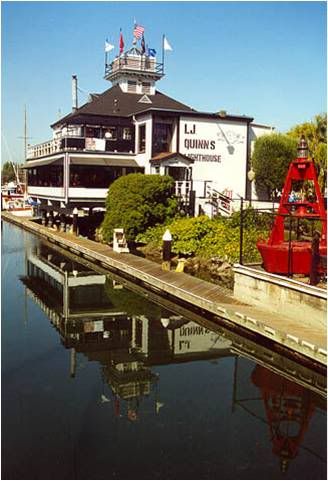

In 1966, an automatic beacon was installed near the lighthouse, and the lighthouse was deactivated. Shortly thereafter, the lantern room was shipped to Santa Cruz were it was installed on the recently constructed Mark Abbott Memorial Lighthouse. The Oakland Harbor Lighthouse was eventually sold to a restaurant firm for $1, but the new owners then had to spend $22,144 to have the Murphy-Pacific Corporation transport the edifice six miles south along the Oakland estuary to its current home at Embarcadero Cove, where it was converted into Quinn's Lighthouse Restaurant and Pub. The restaurant has been open since 1984 and features “contemporary American cuisine.”

Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

.jpg)

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário