Before the Cleveland Dam was built in 1954, the uncontrolled Capilano River plowed into Burrard Inlet near First Narrows churning up tons of silt and rock that even with diligent dredging made wide variations in where the shallows lay. Because of this, as well as the river’s rush of less buoyant fresh water, ships going through the Narrows hugged as tightly as possible to Prospect Point, opposite the river mouth.

Before the Cleveland Dam was built in 1954, the uncontrolled Capilano River plowed into Burrard Inlet near First Narrows churning up tons of silt and rock that even with diligent dredging made wide variations in where the shallows lay. Because of this, as well as the river’s rush of less buoyant fresh water, ships going through the Narrows hugged as tightly as possible to Prospect Point, opposite the river mouth.

On July 25, 1888, the steamship, Beaver slammed into the Prospect Point. The first steamship on the West Coast, the Beaver, built in 1835, was first used by the Hudson Bay Company, then transferred to the Royal Navy in 1863, where for seven years, she was used to survey the British Columbia coast line. Later sold to the British Columbia Towing and Transportation, she was used to tow barges, log booms, and sailing vessels, until she met her demise when her drunken crew ran her aground.Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

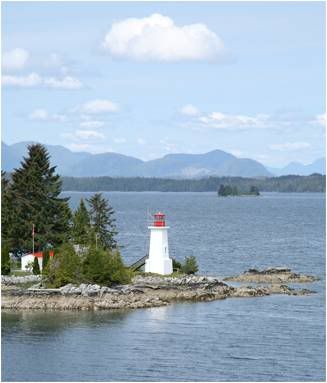

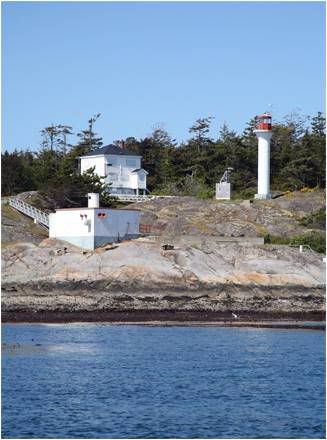

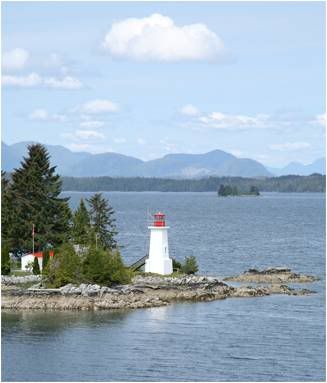

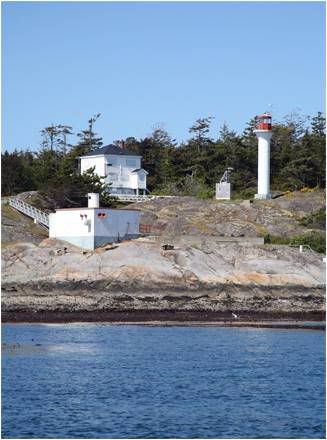

The rear range light is located on Virago Point, the northwest point of Galiano Island, while the front range light is located on Race Point, just across Lighthouse Bay from the rear light.

The rear range light is located on Virago Point, the northwest point of Galiano Island, while the front range light is located on Race Point, just across Lighthouse Bay from the rear light.

Latitude: 49.0129

Longitude: -123.5859Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

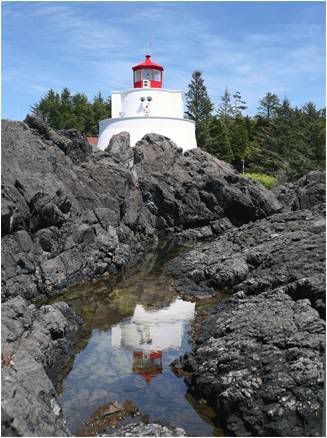

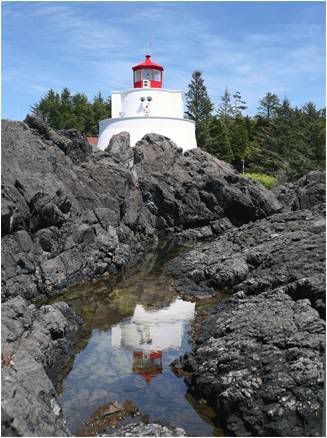

Located in the West Coast Trail Unit of the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve about 15km (9 miles) south of Bamfield.

Located in the West Coast Trail Unit of the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve about 15km (9 miles) south of Bamfield.

Latitude: 48.722092

Longitude: -125.097542Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

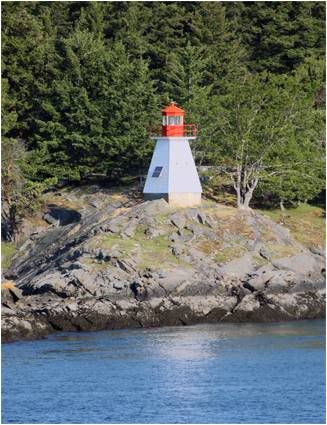

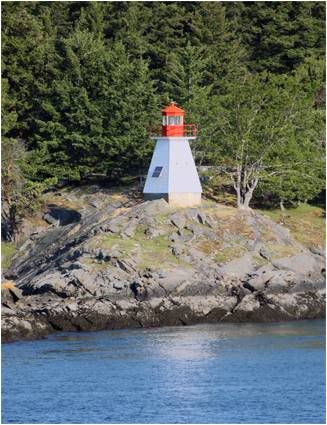

Located on the southeast point of Merry Island, marking the southeast entrance to Welcome Passage.

Located on the southeast point of Merry Island, marking the southeast entrance to Welcome Passage.

Latitude: 49.467486

Longitude: -123.912011Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

Located on the southwest side of Green Island, just south of the U.S./Canada border.

Located on the southwest side of Green Island, just south of the U.S./Canada border.

Latitude: 54.568611

Longitude: -130.70875Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

In 1967, nearly 200 tubbers entered Nanaimo’s first bathtub race, and of those, an amazing forty-seven made it across the Strait of Georgia to Vancouver. The length of the course is still thirty-six miles, but the annual World Championship Bathtub Race now follows a roughly circular route with Entrance Island, a thirty foot high barren outcropping of rock thirteen kilometres (eight miles) outside Nanaimo Harbour, serving as the first checkpoint.

In 1967, nearly 200 tubbers entered Nanaimo’s first bathtub race, and of those, an amazing forty-seven made it across the Strait of Georgia to Vancouver. The length of the course is still thirty-six miles, but the annual World Championship Bathtub Race now follows a roughly circular route with Entrance Island, a thirty foot high barren outcropping of rock thirteen kilometres (eight miles) outside Nanaimo Harbour, serving as the first checkpoint.

Departure Bay and Nanaimo Harbour were busy ports in 1872, shipping coal to destinations throughout the Pacific Rim. In that year alone, 50,000 tons of coal cleared Departure Bay, and with all that shipping, it was inevitable that the Department of Marine and Fisheries would call for a lighthouse to mark the area.

FX Exchange Rate

On January 6, 1875, the Nanaimo Free Press announced that a lighthouse would be built on Entrance Island. As a ship sailed up Georgia Strait, a light on Entrance Island would come into view before the lights at Point Atkinson and the Fraser River were lost. The site for the lighthouse on the northeast corner of the island was the same spot where many years earlier, Imperial surveyors had piled up a heap of stones as a daymark.

The contract for building the light station, along with Berens Light in Victoria Harbour, was awarded to Mr. Louis Baker of Montreal, who committed to construct both lights for $6,900. Baker arrived with much fanfare in August 1875, and promised the light would be up and running by November. But in February 1876, the work was only two-thirds complete, and Baker, after withdrawing all his money, absconded from Nanaimo aboard the steamer Goliath, leaving behind unpaid and angry workmen and suppliers. James Gordon, who was hired to complete the light station, followed suit two months later.

Crooked contractors were not the only thing to plague the construction. Like many a lighthouse, its completion only came after lives were lost in the process. In November 1875, three workmen, M. Longden, Walter Sawyer, and George Furguson, left the island in a “good sea boat” and shortly thereafter found it necessary to tack. The Free Press reported what followed. “In doing so, Longden (who weighs about 225 lbs) failed to change his position. This caused all the weight to be on one side, and the boat filled and turned bottom upwards. The three men managed to get on the keel of the boat. In a short time Sawyer slipped off and was seen no more. After the boat had drifted about a mile in the direction of Lighthouse Island, Longden was seen to drop into the chilling waters. The boat, with Furguson still clinging to the upturned keel, drifted into the Gulf. …The men on the island used their best endeavors to save the unfortunate men, by throwing planks and sticks out towards them, but without avail. There was no other boat on the island.” The boat was later found, but no trace of the three men was ever discovered.

The lighthouse, a square white tower, rising sixty-five feet above high water and attached to a keeper’s dwelling, was declared finished in April 1876 by Arthur Finney, who also oversaw construction of the Point Atkinson lighthouse. It cast its beam for the first time when John Kenny lit its six lamps on the night of Thursday, June 8, 1876.

Kenny resigned six months later, and Robert Gray replaced him. Gray, who served for twenty years, watched in horror in November 1881, when, during a fierce gale, a boat crashed onto the rocks of the island. Gray ran down with a rope to try to assist the passengers, two men, two women, and three children, but a wave struck the stern, overturning the boat, and carried all its occupants out to sea.

In 1891, a fifth-order dioptric apparatus, visible for fourteen miles and equipped with a red sector to warn of Gabriola Reefs, replaced the original light. A larger, fourth-order lens with a twin capillary burner was installed in May 1905, and a revolving lens floating upon a mercury bath replaced this in 1921.

The light station also saw a progression of fog signals. An engine room housing a steam-powered foghorn was built in 1894. In 1915 the signal was converted to diaphones with gasoline engines driving the air compressors.

Keeper Gray’s successor, M.G. Clark saw a canoe carrying two Indians capsize just off the island in July 1902. He and his assistant, John Roberts, quickly launched the station boat and rowed out to save the men. For their good deed, they were each awarded a pair of binoculars and earned a solid, though not sustainable, reputation, which Clark milked for years to come.

Clark and his wife owned a ranch near Orlebar Point on Gabriola Island, a half-mile away from Entrance Island. Mrs. Clark disliked living on Entrance Island, so spent all her time at the ranch. Surprisingly, Keeper Clark spent little time on the island himself, hiring assistants to perform his lighthouse duties and work at the ranch as well.

In a letter to the marine agent, Hugh Brestin described what it was like to be an assistant for Keeper Clark. “When I got there, I was made to feed the chickens, dig his garden, clean his house down for his angel wife.” Brestin was hired in February 1909, and resigned just three months later.

Brestin’s successor was also conscripted as a ranch hand. In November 1910, after working all day at the ranch, he set off in a rowboat at sunset for Entrance Island to tend the light. He never made it. Clark waited until the next day to report the disappearance, causing suspicions to linger for quite some time over the death of the assistant.

A month later, Clark wanted off the island and petitioned for a pension stating that he was in poor health with his eyesight failing to such a point that he could no longer even clean the lamp. The superintendent of lights went to Entrance Island in February and reported that for a man who could barely see, Clark was quite adept at reading fine print and was able to climb the stairs very quickly. His pension request denied, Clark decided that he might be able to keep the light for a few more years.

In June 1911, Allan Pope and his wife answered Clark’s ad for an assistant. They were told Mr. Pope would be expected to “keep things clean and smart about the lighthouse” and tend a flock of chickens, while Mrs. Pope would be responsible for the housework. On finding that Clark really expected them to tend both the ranch and the light, Pope wrote the marine agent, stating that Clark rarely spent time at the lighthouse, Mrs. Pope was expected to do all the Clarks’ laundry as well as clean the lighthouse “top to bottom,” and “they were not the first people that Mr. Clark [had] treated unfair.” Clark soon thereafter fired Pope for being tardy in getting to the ranch in the mornings.

Clark was finally let go in 1913, and his successor, W.E. Morrisey, continued to take advantage of the assistants. Edwin and Bertha Perdue were hired to help at the lighthouse in October 1914, and shortly after, Bertha wrote Victoria asking if there were a set of rules and regulations for lightkeepers that she could read to determine if assistants normally had to stand watch twenty-two hours a day, feed pigs and chickens, and be confined to just two rooms without access to a washroom. The marine agent replied that only the lightkeeper was an employee of the department and assistants were “wholly under the order of the lightkeepers.” After two months at the station with no pay, the nearly starving Perdues engaged the services of an attorney, but this action simply infuriated Morrisey, who promptly ordered the couple off the island.

Since Morrisey, a succession of lightkeepers have faithfully kept the light burning, even while experiencing personal tragedies. One notable example is Michael O’Brien, who in October 1928 had the painful task of radioing Victoria, “My wife drowned last night, rush a relief immediately.”

Sometime around 1970, a cylindrical concrete tower was built a few feet away from the dwelling, replacing the original light. The tower stands 14 metres (45 feet) tall, with a focal plane of 19 metres (62 feet), and flashes a white light every five seconds.

Situated so close to Nanaimo, Entrance Island Lighthouse watches over a large number of boaters and kayakers, and an annual flotilla of bathtubs. The boating community, in turn, keeps its eye on the lighthouse. In 1995, when it was announced that Entrance Island might lose its keepers, more than 100 kayakers, in an act of protest, formed a “human life preserver” around the island.Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

Located on the northern end of Campbell Island along the Seaforth Channel.

Located on the northern end of Campbell Island along the Seaforth Channel.

Latitude: 52.185139

Longitude: -128.111667Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

In July 1792, Captain George Vancouver wound his way northward through the Discovery Passage, where he made the following entry in his logbook on the 15th and 16th of that month.

In July 1792, Captain George Vancouver wound his way northward through the Discovery Passage, where he made the following entry in his logbook on the 15th and 16th of that month.

winds being too light and variable to command the ship against the influence of such rapid tides, we were under the necessity of waiting for the ebb in the afternoon of the following day, when with pleasant weather and a fresh breeze of NW, we weighed about three o’clock turned through the narrows [Seymour Narrows] and having gained about 3 leagues by the time it was nearly dark, we anchored on the western shore in a small on a bottom of sand and mud in 30 fathoms of water to wait the favourable return of the tide. On July 16, 1792 with the assistance of a fresh SW wind and the stream of ebb, we shortly reached Johnstone Straits, passing a point which after our little consort [the HMS Chatham which accompanied the HMS Discovery on Vancouver’s 1791-1795 expedition] I named Point Chatham, situated in Latitude 50 degrees 19 1/2 ‘, Longitude 234 degrees 45’. This point is rendered conspicuous by the confluence of three channels, two of which take their respective direction to the westward and south-eastward towards the ocean, as also by a small bay on each side of it; by three rocky islets close to it; by three rocket islets close to the south of it and by some rocks, over which the sea breaks to the north of it.

And so was this stunning corner of the world described.

A light was first erected at Chatham Point in 1908, to mark the point where the Discovery Passage makes a sharp turn to meet the Johnstone Strait. It was a white steel cylindrical tank on a concrete base surmounted by a white steel pyramidal framework. Built offshore on a rock that stands about five feet above the water, the white flashing light was exhibited twenty-six feet above the sea. The current structure is marked with a green band across the top.

In 1957 a diaphone fog horn operated by air compressed by oil engines was placed on a bluff at the point. Along with the fog signal building, two one-story keeper’s dwellings, and a boathouse were built to complete the light station. Oscar Edwards, who had a long career in the BC light service, became the first keeper when he was transferred from Chrome Island Light Station on February 26, 1957.

The station is still staffed, and the keepers’ work, which includes maintaining the station and collecting marine and weather data is critical to local air and marine traffic.Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

Located at the southern tip of Quadra Island, Cape Mudge Lighthouse marks the southern entrance to Discovery Passage.

Located at the southern tip of Quadra Island, Cape Mudge Lighthouse marks the southern entrance to Discovery Passage.

Though a seemingly tranquil spot passed by ferries and cruise ships headed for Alaska, just a few miles north lie the dreaded Seymour Narrows, which George Vancouver described as “one of the vilest stretches of water in the world.”

Charles Sadilek, whose journals are housed at the Museum of Campbell River, experienced just how wicked the whirlpools of Seymour Narrows could be on June 18, 1875 while aboard the USS Saranac, a three-masted gunboat used as a floating laboratory for the Smithsonian Institute.

Sadilek wrote, “I have never seen an inland body of water more threatening than Seymour Narrows. Even the ocean in a temper has no such ravening aspect.”Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

Off the coast of Japan, a wave forms and then intensifies as it propagates four thousand miles eastward across the Pacific Ocean. High above, westerly winds gather moisture-laden clouds as they blow over the warm waters. When both of these elements meet land for the first time, it is a force to be reckoned with.

Off the coast of Japan, a wave forms and then intensifies as it propagates four thousand miles eastward across the Pacific Ocean. High above, westerly winds gather moisture-laden clouds as they blow over the warm waters. When both of these elements meet land for the first time, it is a force to be reckoned with.

Welcome to the west coast of Vancouver Island, where warm moist air masses, forced upward by the island’s mountain ranges, dump their weight of water on the coastline below as ferocious waves pound the rugged shore.

Captain Harry Scougall and thirty-five others aboard the Pass of Melfort didn’t survive the double blow they were dealt by the elements off Amphitrite Point on Christmas Day, 1905.

The Pass of Melfort and its Captain were not originally scheduled to make their trip to the Northwest that ended that dreadful winter day. The story going around at the time was that the Pass of Branden, a sister ship to the Melfort, had been assigned to make the trip, but when a more favorable charter came in, the owners dispatched the newer Branden to the Antipodes and in its place sent the four-masted, steel-hulled Melfort to Seattle for a load of timber.

That autumn, when the voyage was being arranged, the owners approached Captain Scougall, a fifty-five-year-old retired veteran, and asked if he wouldn’t mind taking the voyage since the current captain appeared to be useless. Captain Scougall, a kind, friendly chap, agreed “out of consideration for his former employers.”

Thirty-eight days after setting off from Panama, the Pass of Melfort met up with Captain Olsen and the British bark Broderick Castle off Southern California. The Captains signaled that they were both headed to the Puget Sound, but when Captain Olsen landed at Port Townsend, he was surprised to learn the Pass of Melfort wasn't there. Olsen speculated that the Pass of Melfort had been caught in the storm he encountered off the Strait of Juan de Fuca, where he had to perform “the toughest bit of sailing he had ever done.”

The Pass of Melfort had missed the Strait and was driven further north by the relentless storm. First Nation people saw a distress rocket over the Uncluth Peninsula on the north shore of Barkley Sound just before dawn on Christmas Day and paddled with the news to the village of Ucluelet.

Both settlers and members of the First Nation scoured the area for signs of a ship, and soon discovered the grim remnants of the Pass of Melfort on a reef, just east of Amphitrite Point, fifty yards from shore. Even as they were combing the shore in hopes of finding survivors, the monstrous seas continued to batter the rocks and “rush into the bay as though in a tide race.” No survivors were found.

Just two weeks before the wreck, the whistling buoy marking the reef had disappeared in heavy seas.

After the Christmas Day tragedy, the shipping industry pressed for a light at Amphitrite Point, and in January 1906, the Department of Marine and Fisheries authorized the construction of a small square wooden tower, painted white and located on the outermost high rock at the point. The tower, which cost $141.54, was equipped with a dioptric lens holding a three-wick, 31-day Wigham lamp. The coxswain of the lifeboat station at Ucluelet was charged with maintaining the light, which the Victoria Times predicted “should prove of incalculable value to a vessel drifting in close to the island shore on such a night as the one in which the Pass of Melfort went to her doom.”

The tower withstood tumultuous tempests for eight years until January 2,1914 when a tidal wave demolished it. The very next night, a replacement lantern was hung from the look-out station situated further back from the bare rock.

Sea captains requested an “up-to-date lighthouse, a wireless station and fog alarm at or near Amphitrite Point,” and construction of the current one-of-kind squat tower began in January 1915.

Originally, the plan was for the tender Leebro to land supplies at the site, but high tides and heavy surf hampered the effort, so instead small vessels were used to lighter supplies ashore. Marine Agent H. L. Roberston, the foreman, wrote, “the last time they attempted the passage with a load in the workboat, they nearly upset & that has put the fear of the Lord into them . . . the surf was breaking right up against the base of the rock & sweeping clear over the top of the high rock to SE of site.” The remaining supplies were wisely landed at the lifeboat station and hauled overland to the construction site. With the steady winter rains, the road turned into “a mass of mud from one end to the other” and within a week had disappeared under six inches of sucking mud.

Despite the weather, the workers kept on schedule, blasting 125 yards of rock, hauling seventy cubic yards of gravel and 420 sacks of cement, and pouring six cubic feet of concrete every three minutes during their fourteen-hour workdays. The lighthouse went into operation in March 1915. It stands six metres (twenty feet) tall, with a focal plane of fifteen metres (fifty feet) and flashes a white light every twelve seconds.

The Ucluelet lifeboat crew maintained the light and horn until July 1918, when their boat was withdrawn from service. Jim Frazer, who had been maintaining the light, took over as keeper for ten dollars a month, a quarter of what he had previously been earning doing the same job for the Naval Service Board.

The squat tower was not a suitable dwelling, with the diaphone taking up half the living space, and poor ventilation causing steam and foul air to pass through the quarters. Frazer lived a mile from the tower and would hike down every night at sunset, in all kinds of weather, to light the lamp, return at midnight to wind the revolving mechanism, then come back at sunrise to extinguish the light. Frazer’s replacement, Frederick Routcliffe, resigned in 1928, claiming “the present quarters at the station are unfit to live in in very wet weather.” A dwelling was finally constructed in 1929, which included a telephone line connected to the village of Tofino.

In Greek mythology, Amphitrite is the sea-goddess wife of Poseidon. Seven ships of the British Royal Navy have borne the name HMS Amphitrite, and the point on Vancouver Island is named after the sixth of these, a twenty-four-gun, 1064-ton vessel, built in Bombay India and stationed in British Columbia from 1851 to 1857.

The unsheltered waters off Amphitrite Point continue to be pounded by severe winter storms, packing thirty to fifty-foot waves, hurricane force winds, and bone chilling rain - an average of three metres (120 inches) annually. Canada’s one-day record rainfall was set near the point on October 6,1967 – 48.9 centimeters (19.3 inches). Many shipwrecks serve as a testament to the unruly elements, including the Pass of Melfort, now a popular diving spot.Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

On Friday morning, March 22, 1895, Frederick Adams sat down and wrote out his will. For the last two years, he had been overseeing the construction of the Legislative Buildings in Victoria, engaging in a cantankerous relationship with the hot-tempered architect Francis Rattenbury. Adams, in his mid-fifties, later that night would board the steamer Velos, with the barge Pilot in tow, and start a 250-mile journey to Haddington Island, near the northeast corner of Vancouver Island to procure a load of stone for the buildings. It would be his last day.

On Friday morning, March 22, 1895, Frederick Adams sat down and wrote out his will. For the last two years, he had been overseeing the construction of the Legislative Buildings in Victoria, engaging in a cantankerous relationship with the hot-tempered architect Francis Rattenbury. Adams, in his mid-fifties, later that night would board the steamer Velos, with the barge Pilot in tow, and start a 250-mile journey to Haddington Island, near the northeast corner of Vancouver Island to procure a load of stone for the buildings. It would be his last day.

The weather had turned sour, and Captain James L. Anderson of the Velos suggested they delay the trip until the storm cleared, but, being behind schedule, Adams was anxious to get under way.

At 9:30 p.m., Captain Anderson, Adams, and five crewmen aboard the Velos, and twenty-four men, mostly laborers and stonemasons, on the Pilot left Victoria Harbour.

Around 10:00 p.m., as they entered Enterprise Channel between Oak Bay and Trial Island, they came up against a fierce southeasterly gale meeting the flood tide. Captain Anderson, thinking the weather too rough to proceed, attempted to turn back to Victoria. In the process of turning, the sea struck the rudder, causing the rudder chains to break and the Velos went broadside in the violent current. Almost before the crew realized the chains were broken, the sea thrust the steamer onto rocks lying out from the mainland, and she quickly sunk, stern first, leaving just a portion of the bow above water. The crew attempted to use the lifeboats, but the steamer filled so quickly, it was impossible to lower them.Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

Located on the southeast end of Kains Island just off the west coast of Vancouver Island at the entrance to Quatsino Sound.

Located on the southeast end of Kains Island just off the west coast of Vancouver Island at the entrance to Quatsino Sound.

Latitude: 50.441194

Longitude: -128.032444Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

While surveying the Gulf Islands in 1861, Captain Daniel Richardson of the Royal Navy named Prevost Island’s eastern extreme Portlock Point after Captain Nathaniel Portlock, who served as a master’s mate aboard the H.M.S. Discovery and H.M.S. Resolution in the 1770s. Nathaniel Portlock would later command the King George on a successful fur-trading expedition to the Pacific Northwest from 1785 to 1788.

While surveying the Gulf Islands in 1861, Captain Daniel Richardson of the Royal Navy named Prevost Island’s eastern extreme Portlock Point after Captain Nathaniel Portlock, who served as a master’s mate aboard the H.M.S. Discovery and H.M.S. Resolution in the 1770s. Nathaniel Portlock would later command the King George on a successful fur-trading expedition to the Pacific Northwest from 1785 to 1788.

Today, thousands of visitors view the diminutive lighthouse on Prevost Island as they comfortably slip past the Portlock Point aboard a ferry, but most will remain ignorant of the pain, suffering, and death that occurred at this seemingly peaceful outpost.

An unmanned stake light was established on Portlock Point in 1890 at the request of George Rudling, captain of the steamer Islander, to help vessels make the transition between Swanson Channel and Trincomali Channel on their way between Vancouver and Victoria. Five years later, G. A. Frost built a square pyramidal wooden tower, with a kitchen attached, on the point at a contract price of $870. The tower stood forty-eight feet tall, from base to vane, and exhibited a fixed white light at a focal plane of seventy-two feet with a red sector covering Enterprise Reef. The light, produced by a dioptric illuminating apparatus of the seventh-order, was put in operation on November 1, 1895.Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

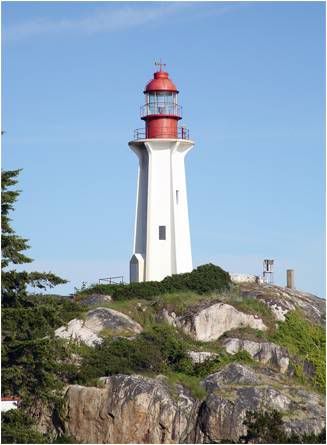

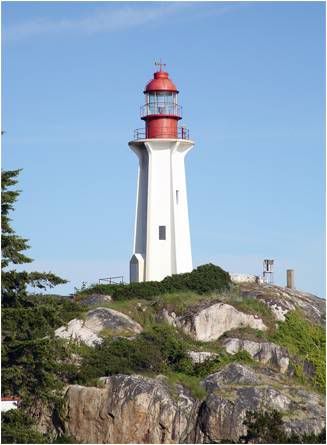

Perched atop a rocky bluff, Point Atkinson Lighthouse winks its watchful eye letting cruise ships and mariners know they have left ‘the city’ and are finally now ‘at sea.’

Perched atop a rocky bluff, Point Atkinson Lighthouse winks its watchful eye letting cruise ships and mariners know they have left ‘the city’ and are finally now ‘at sea.’

Point Atkinson was named by Captain Vancouver, for a “particular friend” on July 4, 1792, when Vancouver sailed past the rocky peninsula aboard the Discovery’s yawl. Today, Lighthouse Park encompasses the point at the entrance of Burrard Inlet and sixty-five hectare (185 acres) of virgin forest, which were set aside in 1881 to serve as a dark backdrop to the lighthouse.

Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

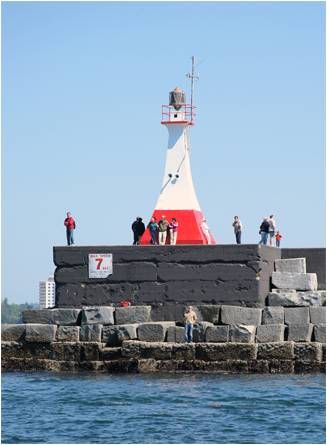

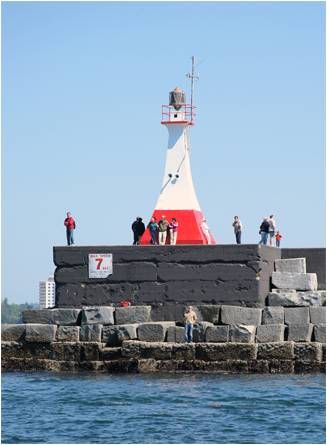

A 1914-1915 appropriation of $1,100,000 provided the initial funding for the construction by the Department of Public Works of the breakwater and two concrete piers at Ogden Point. The rubble mound breakwater has a length of 2,500 feet and is capped with granite blocks and a concrete superstructure. The two concrete piers were originally about 800 feet long and 250 feet wide, with a clearance between them of 300 feet.

A 1914-1915 appropriation of $1,100,000 provided the initial funding for the construction by the Department of Public Works of the breakwater and two concrete piers at Ogden Point. The rubble mound breakwater has a length of 2,500 feet and is capped with granite blocks and a concrete superstructure. The two concrete piers were originally about 800 feet long and 250 feet wide, with a clearance between them of 300 feet.

Ogden Point was named after Peter Skene Ogden (1793 – 1854), a fur trader and explorer employed by the Hudson Bay Company. Roughly 10,000 granite blocks, weighing together over a million tons, were quarried at Hardy Island and shipped to Victoria for use in the breakwater. Completed in 1916, Ogden Point Breakwater was marked the following year by a square, white pyramidal concrete tower that displayed an occulting white light at a height of forty feet above high water. Messrs. Parfitt Brothers erected the tower at a contract price of $1,655, and an unwatched acetylene beacon originally provided the light.

An electrically operated fog alarm was installed on the breakwater in 1919, and in 1926 a cable was laid to supply the needed electricity from shore.

Over the years, the piers at Ogden Point, which were serviced by railway at one time, have been home to a grain terminal, a fish processing and cold storage plant, and a ferry terminal. Various lumber companies also shipped their goods from the piers. Today, a heliport and horse-drawn carriages operate from the piers, but the most visible customers are the mammoth cruise ships that regularly call at the port during the summer months. Cruise ships log over 200 visits to Ogden Point each year, bringing over 400,000 visitors to picturesque Victoria.

Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

Located on southwest point of Lennard Island.

Located on southwest point of Lennard Island.

Latitude: 49.110417

Longitude: -125.923528Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

It seems only fitting that just outside the charming city of Victoria, British Columbia stands the historic and quaint Fisgard Lighthouse.

It seems only fitting that just outside the charming city of Victoria, British Columbia stands the historic and quaint Fisgard Lighthouse.

Fifty years after Captain Vancouver sailed through the Strait of Georgia and named Vancouver Island after himself, the Hudson Bay Company established control of the island and built Fort Victoria, named after Queen Victoria, in 1843. Puget Sound Agricultural Company, a branch of the Hudson Bay Company, started developing large farms near Fort Victoria, and by the time Vancouver Island was established as a colony in 1849, Esquimalt Harbour had become a major port for British ships.

Then came the gold rush. In the late 1850s, gold strikes on the mainland’s Thompson and Fraser rivers brought thousands of prospectors through Victoria, the only source of supplies in the region. Victoria quickly became a boomtown, with a dash of British flavor.

In November 1859, Captain J. Nagle, Victoria’s harbourmaster, seeing the need for an aid to navigation, paid $100 for a lantern and placed it on MacLaughlin Point, at the entrance to Victoria Harbour. Unfortunately, five months later, the lamp’s tubes overheated and melted down, and Nagle had no funds to replace them.

Desiring a replacement for Nagle’s light, Victoria’s merchants petitioned the assembly to allocate funds for a formal lighthouse, but the bill never passed. By then, Captain George Richards, the captain of the HMS Plumper, which was used to survey the British Columbia coast, convinced Nagle that the lighthouses Richards had proposed for Fisgard and Race Rocks were more crucial, and efforts began in earnest to establish these lights.

Commander James Woods, who was surveying Esquimalt Harbour in the brig HMS Pandora in 1846, named the outcropping of volcanic rock just outside the harbour, Fisgard Island, in honor of the assistance he had received from the frigate HMS Fisgard. The island was selected as the site for the lighthouse because it could provide direction for ships to enter Esquimalt Harbour or anchor in Royal Roads, the body of water just south of Fisgard Island, before heading into Victoria. Construction began in 1860, with a design by German-born engineer and architect, Herman Otto Tiedeman, and work overseen by John Wright, a local contractor.

The tower has a two-foot-thick solid granite foundation which is surmounted by fortress like four-foot-thick brick walls and topped with another granite slab, ten inches thick by four feet. The tower stands 14.5 metres (48 feet) tall with a focal plane of 21.5 metres (71 feet). The two-story keeper’s dwelling, also made of brick, has a pair of rooms on both floors each measuring eighteen by fourteen feet. Victoria’s paper, the Colonist, noted that the tower’s spiral staircase, cast in San Francisco, “certainly reflects a great credit on the designer and to see it will amply repay a visit to the Lighthouse.”

While work was underway on the tower, George Davies, aged twenty-eight, was hired in England to be the first full-time keeper on Canada’s West Coast. He signed his yearlong contract on Christmas Eve, 1859, and was given a wage of “150 pounds per annum without rations” along with a dwelling “exclusive of bedding and linen.” He and his wife, Rosina, and three of their four children, boarded the Grecian on January 19, 1860, and set sail for Victoria, a journey that lasted seven months.

Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

Located on Sea Bird Point at the eastern end of Discovery Island.

Located on Sea Bird Point at the eastern end of Discovery Island.

Latitude: 48.4245

Longitude: -123.2258Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

Located in the West Coast Trail Unit of the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve about 26km (16 miles) north of Gordon River.

Located in the West Coast Trail Unit of the Pacific Rim National Park Reserve about 26km (16 miles) north of Gordon River.

Latitude: 48.6115

Longitude: -124.751333Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

Part of the compromise to persuade British Columbia to join the Canada Confederation in 1871 was the agreement to build a transcontinental railroad. Several sites were considered for the railroad’s western terminus, including Port Alberni, situated a third of the way up Vancouver Island at the end of a long inlet that almost cuts the island in two. Cape Beale Lighthouse, the first to be constructed along Vancouver Island’s western shore, was built with that plan in mind and would have saved ships two to three days of sailing to reach Burrard Inlet, near present day Vancouver, where the terminus was eventually set.

Part of the compromise to persuade British Columbia to join the Canada Confederation in 1871 was the agreement to build a transcontinental railroad. Several sites were considered for the railroad’s western terminus, including Port Alberni, situated a third of the way up Vancouver Island at the end of a long inlet that almost cuts the island in two. Cape Beale Lighthouse, the first to be constructed along Vancouver Island’s western shore, was built with that plan in mind and would have saved ships two to three days of sailing to reach Burrard Inlet, near present day Vancouver, where the terminus was eventually set.

Cape Beale, situated at the southern entrance to Barkley Sound forty miles north of Cape Flattery, was named by Captain Charles Barkley in 1787 to honor John Beale, the purser of Barkley’s ship, the Imperial Eagle. Beale, along with 2nd mate Miller and four other crew members were killed by Indians at the Hoh River on the Olympic Peninsula, near Destruction Island later that same year.

In 1872, Benjamin W. Pearse, the assistant surveyor general of the newly formed province, along with several civil engineers, tried unsuccessfully to land on the cape to scout a suitable site for the light. Unwilling to concede defeat, the men attempted to hike six miles overland to the cape from Bamfield, but were thwarted by the impenetrable rainforest that barred their way.

The following year, they succeeded in landing on the rocky cape, which connects to the mainland by a tidal beach, and selected a site for the lighthouse.

Construction began later that year by a crew supervised by Charles Hayward, of Hayward and Jenkinson. The workers and building supplies were transported to the area by the schooner Surprise, which anchored at Dodger Cove, near the Ohiat Indian Village and Trading Post on Diana Island, just north of Cape Beale. From there, Hayward hired First Nations people to raft the materials over to Cape Beale and haul them up the steep incline to the site.

The original light station consisted of a keeper’s house and a thirty-one-foot tapered tower, painted white and topped by a black lantern room enclosing a second-order Fresnel lens.

The light, 167 feet above the sea and visible for nineteen miles, was first lit by Robert Westmoreland, on July 1, 1874. Keeper Westmoreland noticed that the supplies he received did not match the bills of lading and was quite vocal in his speculation that James Cooper, the marine agent in Victoria, might have something to do with it. Cooper sued for slander, and won, costing Westmoreland his job, which he had held for just four years. The marine agent, however, got his due, when further investigation uncovered that Cooper had indeed been skimming off the top. Cooper was arrested but skipped bail and fled the country before a trial.

Westmoreland’s successor, Emmanuel Cox, had earlier served as an overseer on Lord Hamilton’s estate in County Cork, Ireland, but wanting to escape class distinction, had emigrated to California. Upon hearing that Vancouver Island resembled Ireland, Cox relocated there and found work as an agricultural laborer. In 1874, the Governor General of Canada, Lord Dufferin, and Lady Dufferin, the daughter of Lord Hamilton, sought out Cox when they visited Victoria. Appalled to find her old friend working at a level little better than her father’s tenants, Lady Dufferin used her political weight to have him appointed lighthouse keeper at Berens Island in Victoria Harbour. Three years later, Cox was promoted to Cape Beale and moved there with his wife, Frances, and five children, Frances, Annie, Gus, Pattie, and Ernest.

Mrs. Cox never complained of the isolation at Cape Beale or the fact that she was the only white woman for miles around. John Mack, a member of the First Nations, was hired for $5 a month to provide assistance at the station and watch for the Union Jack flying, a signal of distress. He faithfully performed these tasks for an amazing fifty years.

In 1894, John spotted the flag and rushed to the station to discover that his friend, Emmanuel, had died of a heart attack. Next, John paddled his canoe forty miles to Port Alberni to inform Pattie of her father’s death, arriving at two in the morning. Mrs. Cox’s request to replace her husband as keeper was denied, and the fifty-eight- year-old widow was left destitute without claim to her husband’s pension.

The next keeper’s wife rose to fame through her heroic efforts that saved the crew of the 168-foot bark Coloma.

As the sun rose on December 7, 1906, after a wicked night of winter gales, Keeper Thomas Patterson spotted a distressed ship offshore. He awakened his wife, Minnie, and together they kept watch through a telescope. As the bark drifted closer, they could see that the decks were awash and the crew was clinging to the stump of the mizzenmast.

During the night, the winds had toppled trees and snapped the station’s telegraph line, making it impossible to get word of the vessel’s predicament to the light tender Quadra, anchored off Bamfield. Thomas could not leave his post, so Minnie donned a jersey, cap, and her husband’s slippers, and set off into the rain forest that had blocked Pearse’s team thirty-four years earlier. After wading through frigid, waist-deep water at the tidal inlet, bushwacking along the mangled trail, crawling over fallen stumps, sinking knee-deep into swampy bogs, sliding on slippery moss, and at times threading the fallen telegraph wire between her fingers as the only mark to the trail, Minnie finally arrived at the head of Bamfield Inlet. She had hoped to find the rowboat that was usually moored there, but it was gone.

Clinging to the water’s edge she continued undaunted, until deep water would force her back into the forest. After zigzagging another 2 1/2 miles up the inlet, Minnie arrived at the home of Annie Cox McKay, to find that Annie’s husband, John, was away repairing the telegraph line. Without hesitation, the two women launched a skiff and rowed through the rain to the Quadra.

Upon receiving the news, the Quadra weighed anchor and sailed off to help the crew of the Coloma, which was by now, in dire straits. Just after the last of the crew was safely aboard the Quadra’s longboat, the Coloma slammed into a reef and broke up.

Back on shore, Minnie made her way to the telegraph house, where after sipping a cup of hot tea, she announced, “I must get back to my baby.” The two cable operators accompanied her back to the station in their skiff, where along the way, she later said, her legs cramped up so badly, she could hardly move.

Newspapers across the country picked up her story, and she became a bit of a celebrity. When a Seattle Times reporter came to interview her, he brought a check for $315.15 from the women of Vancouver and Victoria, along with personal gifts including a new pair of slippers for Tom. Minnie retrieved the remains of her husband’s old slippers, and holding them up, laughed, and remarked, “I told Tommy that if going over the trail is worth all this money. I had better do it every time it storms so we can retire and get away from here.”

Though her spirit didn’t shatter along the trail, her health did. Minnie never fully recovered and contracted tuberculosis, dying five years later.

By 1958, dry rot had eaten through the original wooden lighthouse, and it was replaced by a thirty-two-foot, steel, skeleton tower topped with an aluminum lantern. An enclosed staircase in the center of the tower provides access to the lantern, where a modern beacon casts forth its light 167 feet above the sea. White slats are mounted on three sides of the tower to serve as a day marker. The old keeper’s dwelling was replaced by three single-family homes, and in 1968 two Airchime fog horns took over the function of the 1908 diaphone.

While Cape Beale still sees an occasional distressed boat, the modern day keepers rarely hike the trail, preferring to radio for help or go inland via boat or helicopter.

Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com

Concílio dos Deuses no Olimpo

Concílio dos Deuses no Olimpo

Quando os Deuses no Olimpo luminoso,

Onde o governo está da humana gente,

Se ajuntam em concílio glorioso

Sobre as cousas futuras do Oriente.

Pisando o cristalino Céu formoso,

Vêm pela Via-Láctea juntamente,

Convocados da parte do Tonante,

Pelo neto gentil do velho Atlante.

Photo & Copyright Carl

Poema Luis de Camoes, Os Lusiadas, Canto I, 20

A Armada do Gama em Alto Mar

A Armada do Gama em Alto Mar

Já no largo Oceano navegavam,

As inquietas ondas apartando;

Os ventos brandamente respiravam,

Das naus as velas côncavas inchando;

Da branca escuma os mares se mostravam

Cobertos, onde as proas vão cortando

As marítimas águas consagradas,

Que do gado de Próteo são cortadas

Photo & Copyright Dan

Poema Luis de Camoes, Os Lusiadas, Canto I, 19

Mas enquanto este tempo passa lento

Mas enquanto este tempo passa lento

De regerdes os povos, que o desejam,

Dai vós favor ao novo atrevimento,

Para que estes meus versos vossos sejam;

E vereis ir cortando o salso argento

Os vossos Argonautas, por que vejam

Que são vistos de vós no mar irado,

E costumai-vos já a ser invocado.

Photo & Copyright Ulrich

Poema Luis de Camoes, Os Lusiadas, Canto I, 18

Em vós se vêm da olímpica morada

Em vós se vêm da olímpica morada

Dos dois avós as almas cá famosas,

Uma na paz angélica dourada,

Outra pelas batalhas sanguinosas;

Em vós esperam ver-se renovada

Sua memória e obras valerosas;

E lá vos tem lugar, no fim da idade,

No templo da suprema Eternidade.Photo & Copyright Vachette

Poema Luis de Camoes, Os Lusiadas, Canto I, 17

Em vós os olhos tem o Mouro frio,

Em vós os olhos tem o Mouro frio,

Em quem vê seu exício afigurado;

Só com vos ver o bárbaro Gentio

Mostra o pescoço ao jugo já inclinado;

Tethys todo o cerúleo senhorio

Tem para vós por dote aparelhado;

Que afeiçoada ao gesto belo e tenro,

Deseja de comprar-vos para genro.

Photo & Copyright YSB

Poema Luis de Camoes, Os Lusiadas, Canto I, 16

Incitação a Dom Sebastião

Incitação a Dom Sebastião

para Novos Feitos Gloriosos

E enquanto eu estes canto, e a vós não posso,

Sublime Rei, que não me atrevo a tanto,

Tomai as rédeas vós do Reino vosso:

Dareis matéria a nunca ouvido canto.

Comecem a sentir o peso grosso

(Que pelo mundo todo faça espanto)

De exércitos e feitos singulares,

De África as terras, e do Oriente os marços,

Photo & Copyright Peter

Poema Luis de Camoes, Os Lusiadas, Canto I, 15

Nem deixarão meus versos esquecidos

Nem deixarão meus versos esquecidos

Aqueles que nos Reinos lá da Aurora

Fizeram, só por armas tão subidos,

Vossa bandeira sempre vencedora:

Um Pacheco fortíssimo, e os temidos

Almeidas, por quem sempre o Tejo chora;

Albuquerque terríbil, Castro forte,

E outros em quem poder não teve a morte.

Photo & Copyright Ihya

Poema Luis de Camoes, Os Lusiadas, Canto I, 14

Pois se a troco de Carlos, Rei de França,

Pois se a troco de Carlos, Rei de França,

Ou de César, quereis igual memória,

Vede o primeiro Afonso, cuja lança

Escura faz qualquer estranha glória;

E aquele que a seu Reino a segurança

Deixou com a grande e próspera vitória;

Outro Joane, invicto cavaleiro,

O quarto e quinto Afonsos, e o terceiro.Photo & Copyright Mardochee

Poema Luis de Camoes, Os Lusiadas, Canto I, 13

Os Heróis Portugueses

Os Heróis Portugueses

Por estes vos darei um Nuno fero,

Que fez ao Rei o ao Reino tal serviço,

Um Egas, e um D. Fuas, que de Homero

A cítara para eles só cobiço.

Pois pelos doze Pares dar-vos quero

Os doze de Inglaterra, e o seu Magriço;

Dou-vos também aquele ilustre Gama,

Que para si de Eneias toma a fama.Photo & Copyright John

Poema Luis de Camoes, Os Lusiadas, Canto I, 12

A classe Albacora é a variante da Marinha Portuguesa da classe de submarinos Daphné de origem francesa.

A classe Albacora é a variante da Marinha Portuguesa da classe de submarinos Daphné de origem francesa.

Em 1964 o Governo Português encomendou a construção de quatro submarinos desta classe aos Estaleiros Dubigeòn, que vieram constituir a 4ª esquadrilha de submarinos da Marinha Portuguesa, sendo operados desde 1967. A nova esquadrilha substituiu a 3ª esquadrilha, que era constituída por submarinos da classe Narval.

Cada submarino foi baptizado com o nome de um animal marinho, cuja inicial (A, B, C ou D) indicava a sua ordem de incorporação.

Com a primeira unidade a entrar ao serviço, a 1 de Outubro de 1967, a Marinha Portuguesa passou a possuir um submarino optimizado para zonas costeiras e oceânicas, para a função de patrulhamento de áreas, especialmente para a Zona Económica Exclusiva.

Está em curso a substituição total da frota desta classe pelos submarinos da classe Tridente.

Data de encomenda 1964

Construção Chantier Dubigeòn

Lançamento 1967

Unidade inicial NRP Albacora (1967)

Unidade final NRP Delfim (1969)

Período de serviço 1967 - atualidade

Tipo Submarino de ataque

Deslocamento 1043 t

Comprimento 57,8 m

Boca 6,8 m

Calado 5,2 m

Propulsão 2 motores diesel SEMT-Pielstick 12 PA4 185 de 1300 cv

2 motores elétricos Jeumont-Schneider de 1,7 MWVelocidade 16 nós

Autonomia 5 000 km a 12 nós

Profundidade 300 m

Armamento 12 tubos de torpedos

Sensores Radar de navegação Kelvin Hughes KH-1007(F)

Sonar de pesquisa ativa e ataque Thomsom-CSF/Thales DSUV-2

Tripulação 54

Text Photo & Copyright Wikipédia

Located on the most easterly and largest rock of Sisters Islets.

Located on the most easterly and largest rock of Sisters Islets.

Latitude: 49.48675

Longitude: -124.577778Photo Text & Copyright www.Lighthousefriends.com